The Sale of the Century: Part 1

When is it a good time to invest in art? This can be a hard question to answer – as any economist will tell you, when it comes to an investment, there are all sorts of factors to take into account, from budget, to background, to timing.

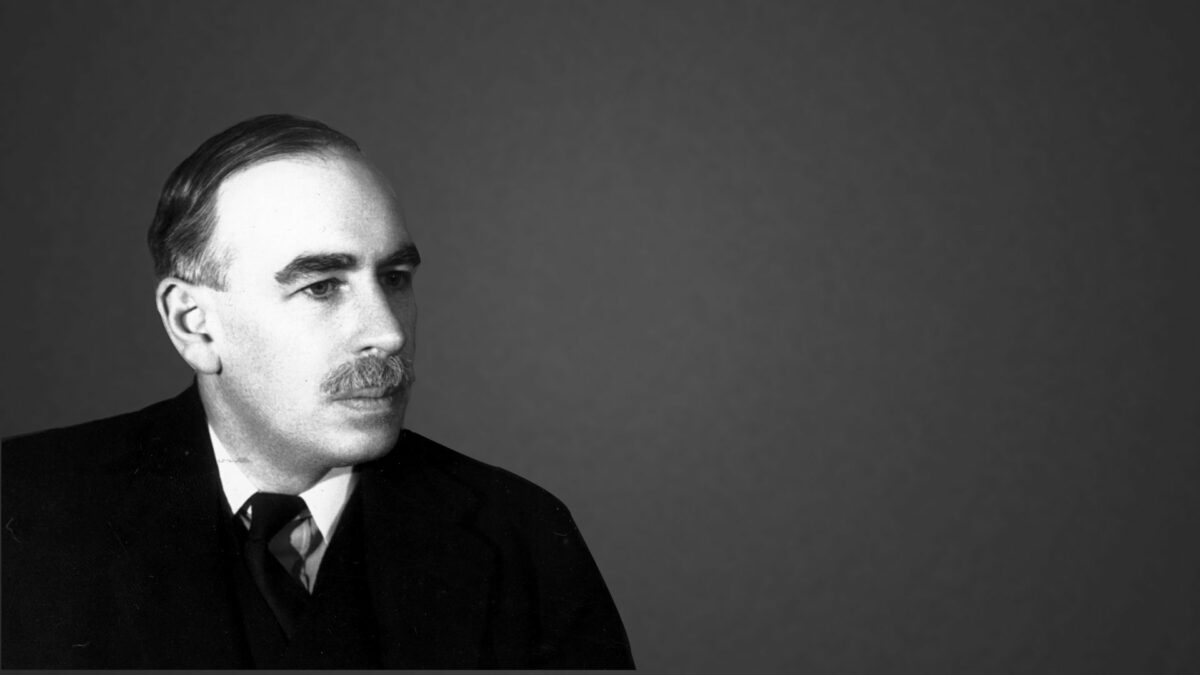

This being the case, it may surprise you to learn that one of the most important art purchases in the history of the UK took place during the least promising circumstances imaginable: at extremely high risk, in the middle of a war, with the sound of artillery shells in the distance. The buyer? One of history’s most famous economists, John Maynard Keynes.

The story of this sale comprises an incredible set of events, involving thousands of pounds of government money, disguises, German super-guns, and a Cezanne in a hedge.

And, as it touches on many principles of art market investment, we’re going to delve into the story itself – as well as the lessons it can hold for art buyers today.

Many will instantly recognise the name John Maynard Keynes. Known as the ‘Father of Macroeconomics’ his influential work has impacted economics on a long-lasting, worldwide scale in a way that few economists have ever achieved. During his lifetime, he held several government positions, and even represented the British Treasury at the Versailles conference in 1919.

What is perhaps less well-known about Keynes, however, was his deep and abiding love for the arts. He was connected with many members of the Bloomsbury Group, and enjoyed an unexpectedly bohemian lifestyle for someone of his position.

It was one of Keynes’ friends in the Bloomsbury Group who set the events of this story in motion. Art Critic Roger Fry told Keynes about an upcoming sale that was to be held in Paris, an auction of impressionist artworks from the collection of the recently deceased Edgar Degas. It would include artworks by Gaugin, Cezanne, Delacoix, Corot, Inges, and Manet.

Keynes decided that this was an opportunity not to be missed – and, incredibly, he convinced the British government, four years into the unprecedented and ongoing conflict of the First World War, to fund the mission. He convinced them that, rather than making another loan to France, they should invest in artworks that – Keynes was certain – would rise in value later.

For the adventure, Keynes enlisted the assistance of Sir Charles Holmes, the director of the National Gallery, to travel with him to Paris and participate in the auction. Travelling to France in 1918 was hardly a risk-free endeavour, and Holmes was also aware that the French might not be happy to sell the artwork to an Englishman if they did arrive safely; he apparently shaved off his moustache in order to disguise himself.

The budget for the auction was £20,000, which is worth just shy of a million pounds today. Keynes knew that the timing of the auction meant prices for the artworks would be much lower

than usual. What he could not have anticipated was that, just as the auction began, a barrage of gunfire started, with the sound of shells sounding over the city from eighty miles away. Many of those who had come to bid at the auction left for safety – and the prices of the lots fell even further. Keynes and Holmes wasted no time in securing an incredible selection of paintings. The artworks purchased included masterpieces such as the Execution of Maximilian by Manet, Flower Piece by Gauguin, and Oedipus and the Sphinx by Ingres.

Not to be left out, Keynes purchased four additional works with his own money, including a still life by Cezanne. Some have argued that the Cezanne might be considered the more important work by contemporary standards, and that Holmes had missed out by not adding the piece to his own purchases. Pommes by Cezanne, however, was far from Keynes’ only significant investment in art in his lifetime; he spent a considerable amount of his private fortune in supporting fine art, dance, theatre, and museums, as well as encouraging public spending for the arts. However, this could easily be considered his most memorable spend: not only a remarkable artwork, but a reminder of what he had achieved with his Parisian adventure.

Returning to Britain in triumph, Keynes seemingly wished to share his tale with those who would most appreciate it – his friends from the Bloomsbury group. He headed directly to the Sussex home shared by artist Vanessa Bell, her husband, art critic Clive Bell, and Keynes’ lover Duncan Grant.

When he arrived at the doorstep, Keynes casually informed his friends that he had left “a Cezanne” in a hedge a little way down the road. Apparently his lift had not been able to drive on the muddy road, so Keynes had stashed his luggage at the edge of a field and walked the rest of the way. The Cezanne was duly retrieved.

This tale, although incredible, is not what Keynes is best known for. He is, after all, primarily remembered for what is still referred to as Keynesian economics. However, to anyone who has studied the life of Keynes, this story will probably seem entirely in character. Keynes took a risk, and it paid off in a huge way: personally, professionally, and as a legacy for the whole of Britain.

Next time, we’re going to look at the points of this story that can be applied to contemporary art sales – although we’ll skip the part where you leave your newly purchased artwork in a hedge.